It’s the second week of May. This time of the year is always heavy with sentimentality; It’s our wedding anniversary, it’s mothers day, and it’s also the anniversary when dad died. Lots of intersecting emotions all in the same few days. So here I am again, thinking about them, once again. Maybe, hopefully, another story of what life has been like to walk through this can be helpful to someone reading it.

Dad grief is now 25. It’s a fully grown adult now, the age at which I got married, which is a weird thought. This grief is perhaps a little more mature, a little more processed, a little less triggered, a little more confident in its views on life, as all good 20 somethings are.

Mum grief, however is 15. A teenager. Somewhat appreciating their teenage years while also yearning to be older and more independent, excited to get a drivers licence and begin assuming the mantle of adulthood.

I don’t know if this helpful imagery to make – Maybe. Maybe not. But the characterisation is interesting to me. Because our griefs grow up with us. Maybe not automatically with age, but certainly with experience and wisdom; we view circumstances with difference, with perhaps with a little more kindness, perhaps with a little more clarity, perhaps with different elements of frustration as they appear.

When I watched Sound of Music as a child, Rolf and Leisl were the highlight – 16 going on 17 was clearly the pinnacle romantic moment of the film. But watching it as an adult, you’ve only got eyes for Maria and the Captain’s relationship. Our perspective can change on the exact same story. Likewise as we move through different seasons and roles in life, we are given the opportunity to see scenes of our story both as child in our childhoods, and also as a grown up and as a parent. You see your world both through the child you were and the adult you are now. And you have some different clarity in places, some different sadness in others.

It’s not a guaranteed better place, when grief grows up. But it can be an interesting and often life giving thing to triangulate our data and experiences. Let me illustrate.

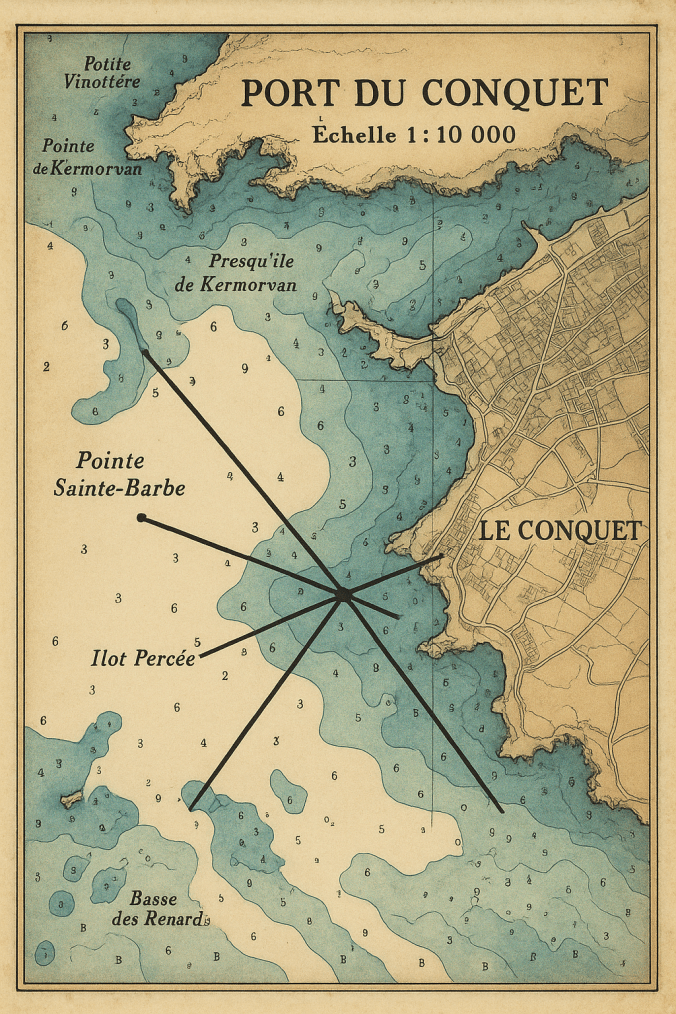

Triangulation: From marine navigation – the use of multiple methods or data sources to develop a comprehensive understanding of phenomena.

Regardless of losing a parent or not, our childhoods are predominatly shaped by the memories and perspective we had ‘then’. Think on a time when you were hurt, or we were embarrassed, anxious or afraid. Maybe you remember what it felt like, what it meant about who you were, and what people thought and think of you. Maybe someone was kind to you in that moment and helped you out. Or maybe you didn’t receive the support you needed. Likely, however, if the pain is still present, it is reasonable to assume that there was something (or someone) in the story that wasn’t resolved, was lacking, or is still triggering.

Now let’s triangulate the data. Imagine yourself as a parent or a loved one to yourself. And particularly, as someone who you needed in that moment. How does your perspective shift of what you did, and who you are? What changes when we see ourselves through someone that you needed in that moment? Compassion usually comes. Grace usually comes with it. Perspective gives us more knowledge to understand ourselves and those around us. And maybe with that knowledge, we can be the person or parent to ourselves, in even a small way, in the way that we need[ed], now.

The same process can be done when we project our adult selves into the lives of those we may have lost; or even with our family who live around us. While the pain of adulting without [my] adults is still present, the gift parenting and partnering has given me is to imagine myself as my parents’ peer. What was it like to bring up me and my family in their context? What was it like to lose your partner in such a way? What was it like to walk in their shoes of creating the big lives that they were pursuing? As we see ourselves in our story as children, likewise we always fix the grown ups in our lives as [proper] grown ups, a couple generations above, 20 years irrelevant. Imagining them instead as surely-yet-hopeful teenagers, 20 confident-energetic somethings, 30 tired-but-working at it parents, 40 wiser and funny somethings. Then add yourself as a guest and friend in their midst. It can be a cool thing. It brings a whole different set of data to the mix.

I would add a caveat that this process isn’t merely ‘walking a mile in someone else’s shoes’, a message that is preached often in our lives; the distinction here is that you are using your perspective as one in a different stage of life, someone with experiences of adulting, of parenting, of partnering, of working, of mentoring, of leading, as a resource. We can imagine ourselves as a friend, peer, or helpful adult in the scenes of our biographies, and see what wisdom we can offer to our younger selves and the other characters of our histories.

I’ll finish with a story; my nephew has fallen in love with vintage audio tech, and came across a tape recently of my parents sending a Christmas audio ‘letter’ home to their family while they were living in Los Angeles in the 1970s. As we listened to it, I had the joy of hearing Mum and Dad speak not as the age they are usually fixed in my mind, but as 25 and 28! Instead of the narrative of sickness, stress or depression that dominate many of the ‘last’ stories of my parents, what we heard was a young couple, unburdened, recently married, going on an adventure. No one in their respective families had been to America before, so they spent time detailing the scenery and their favourite parts of their city. They had discovered Mexican food and described burritos to their family as meat and cheese wrapped in flat pastry?! They spoke of their colleagues and their Christmas plans. They were bantering with each other and spoke excitedly of their hopes for the next few months. I loved it, hearing their voices young and full of life. The best thing, however was our kids getting to hear their Grandparent’s voices too, getting a better sense of the people that help shape who they are. What a gift it is, to know a little more of who they were then, as who I am now.

Lastly friends, I will say that Data Triangulation doesn’t change what [has] happened. This process is not trying to make small what you’ve gone through in your life. But it can invite some kinder voices to the mix. Our griefs grow up with us. As many of you would know; grief doesn’t go away as the years go on. In many ways, nor should it; grief is a representation of the love we had for someone, or the love of a life and potential that went unfulfiled.

The gift that time can bring, perhaps, is opportunities to greet it, meet it, and see our grief – and lives – from who we are now rather than just from a single and fixed point of view; the power of triangulating our story.

x

love this, thank you for writing it so eloquently ♥️

Thanks Jess! Appreciate it xx